Szerkesztő:BélaBéla/Ariel (hold)

| Ariel | |

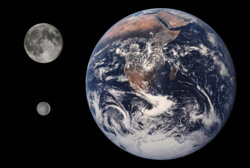

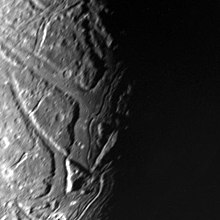

[[Fájl: |250px|Az Ariel a Voyager–2 felvételén. A kép 1986-ban készült, megközelítőleg 130 000 km-es távolságból.]] |250px|Az Ariel a Voyager–2 felvételén. A kép 1986-ban készült, megközelítőleg 130 000 km-es távolságból.]] | |

| Az Ariel a Voyager–2 felvételén. A kép 1986-ban készült, megközelítőleg 130 000 km-es távolságból. | |

| Felfedezése | |

| Felfedező | William Lassell |

| Felfedezés ideje | 1851. október 24. |

| Alternatív név | Uránusz I |

| Pályaadatok | |

| Fél nagytengely | 191 020 km |

| Pálya excentricitása | 0,0012 |

| Keringési periódus | 5,52 nap |

| Inklináció | 0,260 (az Uránusz egyenlítőjéhez) |

| Anyabolygó | Uránusz |

| Fizikai tulajdonságok | |

| Átlagos átmérő | 578,9±0,6 km (a földi 0,0908-szorosa) |

| Felszín területe | 4 211 300 km2 |

| Térfogat | 812 600 000 km3 |

| Tömeg | (1,353±0,120)×1021 kg (a földi 0,000226-szerese) |

| Átlagos sűrűség | 2,061g/cm³ |

| Felszíni gravitáció | 0,27 m/s² |

| Szökési sebesség | 0,558 km/s |

| Forgási periódus | megegyezik a keringési periódussal |

| Albedó | 0,53 |

| Felszíni hőmérséklet | 60 K (-213 °C) |

| Látszólagos fényesség | 14,4 |

| Sablon • Wikidata • Segítség | |

Az Ariel a negyedik legnagyobb az Uránusz huszonhét ismert holdja közül. Az Uránusz egyenlítői síkjában kering, amely szinte merőleges a bolygó pályasíkjára, ezért erőteljes évszakok váltakoznak rajta. Az Arielt William Lassell fedezte fel 1851 októberében és tőle származik a hold neve is. Az égitestről való jelenlegi tudásunk nagy része egyetlen űrszondától, a Voyager–2-től származik, mely 1986-ban repült el az Uránusz mellett, és az Ariel felszínének körülbelül 35%-át feltérképezte.

Az Ariel az Uránusz tizenötödik holdja, a nagy holdak közül a bolygóhoz második legközelebbi, közülük a Miranda utáni legkisebb. A Naprendszer összes ismert holdja közül a 14. legnagyobb. A feltételezések szetint anyagát egyenlő arányban alkotja jég és szikla. Az Uránusz többi holdjához hasonlóan az Ariel feltehetőleg egy akkréciós korongból keletkezett, mely a bolygót keletkezése után ölelte körül. Az Ariel belső szerkezete differenciált, a belső, sziklás magot egy jégköpeny veszi körbe. A hold felszíne kráterekkel tarkított, a hatalmas, keresztül-kasul futó árkok és vetődéses rézsűk arra utalnak, hogy a hold múltjában fontos szerepe lehetett a tektonikus mozgásoknak.

Felfedezés és elnevezés[szerkesztés]

Az Arielt William Lassell fedezte fel 1851 október 24-én és egy karakterről nevezte el Alexander Pope A fürtrablás és William Shakespeare A vihar című művéből.

Mind az Arielt, mind a nála valamivel nagyobb Umbrielt Lassel fedezte fel 1851 október 24-én,[1][2] bár William Herschel, az Uránusz két legnagyobb holdjának, az Oberonnak és a Titániának a felfedezője négy másik holdról is beszámolt,[3] de ez az állítás soha nem nyert bizonyítást és feltehetően hamis volt.[4][5][6]

A holdat néha Uránusz I-nek is nevezik.[2]

Keringés[szerkesztés]

Az Uránusz öt nagy holdja közül az Ariel a második legbelső, körülbelül 190 000 kilométerre kering a bolygótól.[m 1] Pályájának excentricitása kicsi, pályája nagyon kis mértékben dőlt az Uránusz egyenlítői síkjához.[7] Keringési periódusa nagyjából 2,5 földi nap, ami megegyezik a forgási idejével. Ez azt jelenti, hogy a hold kötött keringésű, vagyis mindig ugyanazt azarcát mutatja a bolygó felé.[8] Az Ariel pályája teljes egészében az Uránusz magnetoszférájába esik.[9] Azoknak az atmoszféra nélküli holdaknak, melyek egy bolygó magnetoszférájában keringenek a követő féltekéjük - vagyis ami a keringés irányával ellentétes irányba néz - a holddal együtt keringő magnetoszférikus plazmával vannak sújtva.[10] Ez a követő félteke sötétebb színéhez vezethet, melyet az Oberon kivételével az Uránusz összes holdjánál megfigyeltek.[9] Az Ariel a magnetoszférából töltött részecskéket ejt foglyul csökkentve azok számát a pályája mentén.[11]

Mivel az Ariel az Uránuszhoz hasonlóan teljesen az oldalára van dőlve, így napforduló idején az egyik féltekéje teljesen a Nap felé néz, a másik pedig teljesen elfordul tőle. Ez szélsőséges évszakváltakozást eredményez az égitesten: ahogyan a Föld sarkvidékein állandó éjszaka, vagy nappal van a napfordulók közelében, az Ariel pólusain egy fél uránuszi évig (vagyis 42 földi évig) tart egy nappal, vagy éjszaka.[9] A Voyager-2 1986-os látogatása egybeesett a déli félteke nyári napfordulójával, ekkor majdnem a teljes északi félgömb sötétségben volt. 42 évente, az uránuszi napéjegyenlőség idején, amikor a bolygó az egyenlítőjét mutatja a Föld felé, lehetővé válnak okkultációk (fedések) a holdak között. Több ilyen okkultációt megfigyeltek 2006 és 2007 között, köztük az Ariel Umbriel általi fedését 2007 augusztus 19-én.[12]

Jelenleg az Ariel nem áll keringési rezonanciában egy Uránusz-holddal sem, bár a múltban feltehetően fennált egy 5:3 rezonancia közte és a Miranda között, mely részben felelős lehetett a Miranda fűtéséért.[13] Része lehetett egy 4:1 rezonanciában is a Titániával, melyből később megszökött.[14]

Összetétel és belső szerkezet[szerkesztés]

Az Ariel az Uránusz negyedik legnagyobb holdja, és lehetséges hogy a harmadik legnagyobb tömegű.[m 2] Sűrűsége 1,66 g/cm3,[16], ebből arra következtethetünk, hogy nagyjából egyenlő arányban tartalmaz vízjeget és sűrűbb, nem-jeges anyagokat.[17] Ez utóbbiak lehetnek sziklás kőzetek, vagy egyfajta nehéz szerves vegyületekből álló massza, az úgynevezett tholin.[8] A víz jelenlétét infravörös spektroszkópiás vizsgálatok igazolják, melyek kristályos vízjeget mutattak ki a hold felszínén.[9] A vízjég abszorpciós vonalai erősebbek a bolygó vezető féltekéjén, mint a követőn,[9] ennek az eltérésnek az oka pontosan nem ismert, de lehetséges, hogy a követő féltekének az Uránusz magnetoszférájából származó töltött részecskékkel való erősebb bombázásának tudható be.[9]

A vízjég mellet a másik vegyület, melyet infravörös spektroszkópiával kimutattak a hold felszínén a szén-dioxid, mely főként a követtő féltekén koncentrálódik. Az Ariel volt az első az Uránusz holdjai közül, ahol kimutatták ezt a vegyületet.[9] A szén-dioxid eredete nem tisztázott. Lehetséges, hogy helyileg képződik karbonátokból vagy szerves vegyületekből ibolyántúli sugárzás, vagy az Uránusz magnetoszférájából érkező nagy energiájú részecskék hatására. Ez az elmélet megmagyarázná a követő féltekén való nagyobb CO2 koncentációt, mivel a követő félteke jobban ki van téve a magnetoszférikus hatásnak, mint a vezető félteke. A holdon lévő szén-dioxid származhat a jég által csapdába ejtett szén-dioxid kigázosodásából, mely a hold korábbi geológiai aktivitásához köthető.[9]

Az Ariel méretéből, összetételéből és az oldott sók és ammónia feltételezett jelenlétéből, melyek csökkentik a víz olvadáspontját, arra következtethetünk, hogy az Ariel belseje két rétegre differenciálódott: egy sziklás magra, melyet egy jeges köpeny vesz körül.[17] Ebben az esetben a mag átmérője 372 kilométer, ami körülbelül 64%-a a hold átmérőjének, tömege pedig hozzávetőlegesen 56%-a a hold teljes tömegének. A hold központjában a nyomás 0,3 GPa körüli lehet.[17] A jeges köpeny állapota nem tisztázott, de egy felszín alatti óceán létezése kizárható.[17]

Felszín[szerkesztés]

Albedo és szín[szerkesztés]

Ariel is the most reflective of Uranus's moons.[18] Its surface shows an opposition surge: the reflectivity decreases from 53% at a phase angle of 0° (geometrical albedo) to 35% at an angle of about 1°. The Bond albedo of Ariel is about 23%—the highest among Uranian satellites.[18] The surface of Ariel is generally neutral in color.[19] There may be an asymmetry between the leading and trailing hemispheres;[20] the latter appears to be redder than the former by 2%.[a] Ariel's surface generally does not demonstrate any correlation between albedo and geology on the one hand and color on the other hand. For instance, canyons have the same color as the cratered terrain. However, bright impact deposits around some fresh craters are slightly bluer in color.[19][20] There are also some slightly blue spots, which do not correspond to any known surface features.[20]

Felszíni vonások[szerkesztés]

The observed surface of Ariel can be divided into three terrain types: cratered terrain, ridged terrain and plains.[21] The main surface features are impact craters, canyons, fault scarps, ridges and troughs.[22]

The cratered terrain, a rolling surface covered by numerous impact craters and centered on Ariel's south pole, is the moon's oldest and most geographically extensive geological unit.[21] It is intersected by a network of scarps, canyons (graben) and narrow ridges mainly occurring in Ariel's mid-southern latitudes.[21] The canyons, known as chasmata,[23] probably represent graben formed by extensional faulting, which resulted from global tensional stresses caused by the freezing of water (or aqueous ammonia) in the moon's interior (see below).[8][21] They are 15–50 km wide and trend mainly in an east- or northeasterly direction.[21] The floors of many canyons are convex; rising up by 1–2 km.[23] Sometimes the floors are separated from the walls of canyons by grooves (troughs) about 1 km wide.[23] The widest graben have grooves running along the crests of their convex floors, which are called valles.[8] The longest canyon is Kachina Chasma, at over 620 km in length (the feature extends into the hemisphere of Ariel that Voyager 2 did not see illuminated).[22][24]

The second main terrain type—ridged terrain—comprises bands of ridges and troughs hundreds of kilometers in extent. It bounds the cratered terrain and cuts it into polygons. Within each band, which can be up to 25 to 70 km wide, are individual ridges and troughs up to 200 km long and between 10 and 35 km apart. The bands of ridged terrain often form continuations of canyons, suggesting that they may be a modified form of the graben or the result of a different reaction of the crust to the same extensional stresses, such as brittle failure.[21]

The youngest terrain observed on Ariel are the plains: relatively low-lying smooth areas that must have formed over a long period of time, judging by their varying levels of cratering.[21] The plains are found on the floors of canyons and in a few irregular depressions in the middle of the cratered terrain.[8] In the latter case they are separated from the cratered terrain by sharp boundaries, which in some cases have a lobate pattern.[21] The most likely origin for the plains is through volcanic processes; their linear vent geometry, resembling terrestrial shield volcanoes, and distinct topographic margins suggest that the erupted liquid was very viscous, possibly a supercooled water/ammonia solution, with solid ice volcanism also a possibility.[23] The thickness of these hypothetical cryolava flows is estimated at 1–3 km.[23] The canyons must therefore have formed at a time when endogenic resurfacing was still taking place on Ariel.[21]

Ariel appears to be fairly evenly cratered compared to other moons of Uranus;[8] the relative paucity of large craters[b] suggests that its surface does not date to the Solar System's formation, which means that Ariel must have been completely resurfaced at some point of its history.[21] Ariel's past geologic activity is believed to have been driven by tidal heating at a time when its orbit was more eccentric than currently.[14] The largest crater observed on Ariel, Yangoor, is only 78 km across,[22] and shows signs of subsequent deformation. All large craters on Ariel have flat floors and central peaks, and few of the craters are surrounded by bright ejecta deposits. Many craters are polygonal, indicating that their appearance was influenced by the preexisting crustal structure. In the cratered plains there are a few large (about 100 km in diameter) light patches that may be degraded impact craters. If this is the case they would be similar to palimpsests on Jupiter's moon Ganymede.[21] It has been suggested that a circular depression 245 km in diameter located at 10°S 30°E is a large, highly degraded impact structure.[26]

Origin and evolution[szerkesztés]

Ariel is thought to have formed from an accretion disc or subnebula; a disc of gas and dust that either existed around Uranus for some time after its formation or was created by the giant impact that most likely gave Uranus its large obliquity.[27] The precise composition of the subnebula is not known; however, the higher density of Uranian moons compared to the moons of Saturn indicates that it may have been relatively water-poor.[c][8] Significant amounts of carbon and nitrogen may have been present in the form of carbon monoxide (CO) and molecular nitrogen (N2) instead of methane and ammonia.[27] The moons that formed in such a subnebula would contain less water ice (with CO and N2 trapped as clathrate) and more rock, explaining the higher density.[8]

The accretion process probably lasted for several thousand years before the moon was fully formed.[27] Models suggest that impacts accompanying accretion caused heating of Ariel's outer layer, reaching a maximum temperature of around 195 K at a depth of about 31 km.[28] After the end of formation, the subsurface layer cooled, while the interior of Ariel heated due to decay of radioactive elements present in its rocks.[8] The cooling near-surface layer contracted, while the interior expanded. This caused strong extensional stresses in the moon's crust reaching estimates of 30 MPa, which may have led to cracking.[29] Some present-day scarps and canyons may be a result of this process,[21] which lasted for about 200 million years.[29]

The initial accretional heating together with continued decay of radioactive elements and likely tidal heating may have led to melting of the ice if an antifreeze like ammonia (in the form of ammonia hydrate) or some salt was present.[28] The melting may have led to the separation of ice from rocks and formation of a rocky core surrounded by an icy mantle.[17] A layer of liquid water (ocean) rich in dissolved ammonia may have formed at the core–mantle boundary. The eutectic temperature of this mixture is 176 K.[17] The ocean, however, is likely to have frozen long ago. The freezing of the water likely led to the expansion of the interior, which may have been responsible for the formation of the canyons and obliteration of the ancient surface.[21] The liquids from the ocean may have been able to erupt to the surface, flooding floors of canyons in the process known as cryovolcanism.[28]

Thermal modeling of Saturn's moon Dione, which is similar to Ariel in size, density and surface temperature, suggests that solid state convection could have lasted in Ariel's interior for billions of years, and that temperatures in excess of 173 K (the melting point of aqueous ammonia) may have persisted near its surface for several hundred million years after formation, and near a billion years closer to the core.[21]

Observation and exploration[szerkesztés]

The apparent magnitude of Ariel is 14.8;[30] similar to that of Pluto near perihelion. However, while Pluto can be seen through a telescope of 30 cm aperture,[31] Ariel, due to its proximity to Uranus's glare, is often not visible to telescopes of 40 cm aperture.[32]

The only close-up images of Ariel were obtained by the Voyager 2 probe, which photographed the moon during its flyby of Uranus in January 1986. The closest approach of Voyager 2 to Ariel was 127 000 km (79 000 mi)—significantly less than the distances to all other Uranian moons except Miranda.[33] The best images of Ariel have a spatial resolution of about 2 km.[21] They cover about 40% of the surface, but only 35% was photographed with the quality required for geological mapping and crater counting.[21] At the time of the flyby the southern hemisphere of Ariel (like those of the other moons) was pointed towards the Sun, so the northern (dark) hemisphere could not be studied.[8] No other spacecraft has ever visited the Uranian system, and no mission to Uranus and its moons is planned.[34] The possibility of sending the Cassini spacecraft to Uranus was evaluated during its mission extension planning phase.[35] It would take about twenty years to get to the Uranian system after departing Saturn.[35]

Transits[szerkesztés]

On 26 July 2006, the Hubble Space Telescope captured a rare transit made by Ariel on Uranus, which cast a shadow that could be seen on the Uranian cloud tops. Such events are rare and only occur around equinoxes, as the moon's orbital plane about Uranus is tilted 98° to Uranus's orbital plane about the Sun.[36] Another transit, in 2008, was recorded by the European Southern Observatory.[37]

Források[szerkesztés]

- ↑ Lassell, W. (1851). „On the interior satellites of Uranus”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 12, 15–17. o.

- ↑ a b doi:10.1086/100198

- ↑ doi:10.1098/rstl.1798.0005

- ↑ Struve, O. (1848). „Note on the Satellites of Uranus”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 8 (3), 44–47. o.

- ↑ Holden, E. S. (1874). „On the inner satellites of Uranus”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 35, 16–22. o.

- ↑ Lassell, W. (1874). „Letter on Prof. Holden's Paper on the inner satellites of Uranus”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 35, 22–27. o.

- ↑ Planetary Satellite Mean Orbital Parameters. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j doi:10.1126/science.233.4759.43 (See pages 58–59, 60–64)

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.04.016

- ↑ doi:10.1126/science.233.4759.85

- ↑ doi:10.1126/science.233.4759.97

- ↑ doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2008.12.010

- ↑ doi:10.1016/0019-1035(90)90125-S

- ↑ a b doi:10.1016/0019-1035(90)90024-4

- ↑ Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters. Jet Propulsion Laboratory (Solar System Dynamics). [2009. május 22-i dátummal az eredetiből archiválva]. (Hozzáférés: 2009. május 28.)

- ↑ doi:10.1086/116211

- ↑ a b c d e f doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.005

- ↑ a b doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6596

- ↑ a b c (1991) „A search for spectral units on the Uranian satellites using color ratio images”. Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, 21st, Mar. 12–16, 1990: 473–489, Houston, TX, United States: Lunar and Planetary Sciences Institute.

- ↑ a b c d doi:10.1016/0019-1035(91)90064-Z

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p doi:10.1038/327201a0

- ↑ a b c Nomenclature Search Results: Ariel. Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology. (Hozzáférés: 2010. november 29.)

- ↑ a b c d e doi:10.1029/90JB01604 (See pages 1893–1896)

- ↑ Stryk, Ted: Revealing the night sides of Uranus' moons. The Planetary Society Blog. The Planetary Society, 2008. március 13. (Hozzáférés: 2012. február 25.)

- ↑ Plescia, J. B. (1987). „Geology and Cratering History of Ariel”. Abstracts of the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 18, 788. o.

- ↑ doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.05.009

- ↑ a b c doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20031515

- ↑ a b c doi:10.1029/JB093iB08p08779

- ↑ a b doi:10.1029/91JE01401

- ↑ doi:10.1016/j.pss.2008.02.034

- ↑ This month Pluto's apparent magnitude is m=14.1. Could we see it with an 11" reflector of focal length 3400 mm?. Singapore Science Centre. [2005. november 11-i dátummal az eredetiből archiválva]. (Hozzáférés: 2007. március 25.)

- ↑ Sinnott, Roger W.; Ashford, Adrian: The Elusive Moons of Uranus. Sky & Telescope. (Hozzáférés: 2011. január 4.)

- ↑ doi:10.1029/JA092iA13p14873

- ↑ Missions to Uranus. NASA Solar System Exploration, 2010. (Hozzáférés: 2014. november 13.)

- ↑ a b Bob Pappalardo: Cassini Proposed Extended-Extended Mission (XXM) (PDF), 2009. március 9. (Hozzáférés: 2011. augusztus 20.)

- ↑ Uranus and Ariel. Hubblesite (News Release 72 of 674), 2006. július 26. (Hozzáférés: 2006. december 14.)

- ↑ Uranus and satellites. European Southern Observatory, 2008. (Hozzáférés: 2010. november 27.)

Forráshivatkozás-hiba: a <references> címkében definiált „mw dict” nevű <ref> címke nem szerepel a szöveg korábbi részében.

Forráshivatkozás-hiba: a <references> címkében definiált „Thomas 1988” nevű <ref> címke nem szerepel a szöveg korábbi részében.

Forráshivatkozás-hiba: a <references> címkében definiált „Hanel Conrath et al. 1986” nevű <ref> címke nem szerepel a szöveg korábbi részében.

Forráshivatkozás-hiba: a <references> címkében definiált „Lassell 1852” nevű <ref> címke nem szerepel a szöveg korábbi részében.

Forráshivatkozás-hiba: a <references> címkében definiált „Harrington 2011” nevű <ref> címke nem szerepel a szöveg korábbi részében.

Forráshivatkozás-hiba: a <references> címkében definiált „Kuiper 1949” nevű <ref> címke nem szerepel a szöveg korábbi részében.

Forráshivatkozás-hiba: a <references> címkében definiált „NASA Solar System Exploration 2014” nevű <ref> címke nem szerepel a szöveg korábbi részében.

Külső hivatkozások[szerkesztés]

- Ariel profile at NASA's Solar System Exploration site

- AN, 33 (1852) 257/258

- Ariel basemap derived from Voyager images

- Ariel page (including labelled maps of Ariel) at Views of the Solar System

- NASA archive of publicly released Ariel images

- Paul Schenk's 3D images and flyover videos of Ariel and other outer solar system satellites

- Ariel nomenclature from the USGS Planetary Nomenclature web site

- Ted Stryk: Revealing the night sides of Uranus' moons

Fordítás[szerkesztés]

Forráshivatkozás-hiba: <ref> címkék léteznek a(z) „m” csoporthoz, de nincs hozzá <references group="m"/>

Forráshivatkozás-hiba: <ref> címkék léteznek a(z) „lower-alpha” csoporthoz, de nincs hozzá <references group="lower-alpha"/>