„A dinoszauruszok mérete” változatai közötti eltérés

| [ellenőrzött változat] | [ellenőrzött változat] |

Nincs szerkesztési összefoglaló |

Nincs szerkesztési összefoglaló |

||

| 8. sor: | 8. sor: | ||

# ''[[Amphicoelias]]'': 122,4 tonna<ref name=KC06/> |

# ''[[Amphicoelias]]'': 122,4 tonna<ref name=KC06/> |

||

# ''[[Argentinosaurus]]'': 50- |

# ''[[Argentinosaurus]]'': 50-90 tonna<ref name="G.S.Paul2010"/><ref name="Bensonetal2014"/> |

||

# ''[[Futalognkosaurus]]'': (az ''Argentinosaurushoz'' és a ''Puertasaurushoz'' hasonló)<ref name=calvoetal2007/> |

# ''[[Futalognkosaurus]]'': (az ''Argentinosaurushoz'' és a ''Puertasaurushoz'' hasonló)<ref name=calvoetal2007/> |

||

# ''[[Puertasaurus]]'': (az ''Argentinosaurushoz'' hasonló)<ref name=NSCA05/> |

# ''[[Puertasaurus]]'': (az ''Argentinosaurushoz'' hasonló)<ref name=NSCA05/> |

||

| 166. sor: | 166. sor: | ||

20 tonnát meghaladó tömegű sauropodák: |

20 tonnát meghaladó tömegű sauropodák: |

||

# ''[[Amphicoelias]]'': 122,4 tonna<ref name=KC06/> |

# ''[[Amphicoelias]]'': 122,4 tonna<ref name=KC06/> |

||

# ''[[Argentinosaurus]]'': 50-90 tonna<ref name="G.S.Paul2010"/><ref name="Bensonetal2014">{{cite journal | last1 = Benson | first1 = RBJ | last2 = Campione | first2 = NE | last3 = Carrano | first3 = MT | last4 = Mannion | first4 = PD | last5 = Sullivan | first5 = C et al. | year = 2014 | title = Rates of Dinosaur Body Mass Evolution Indicate 170 Million Years of Sustained Ecological Innovation on the Avian Stem Lineage | url = | journal = PLoS Biol | volume = 12 | issue = 5| page = e1001853 | doi = 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001853 | author6 = and others | last7 = Evans | first7 = David C. | displayauthors = 5 }}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

# ''[[Futalognkosaurus]]'': (az ''Argentinosaurushoz'' és a ''Puertasaurushoz'' hasonló)<ref name=calvoetal2007/> |

# ''[[Futalognkosaurus]]'': (az ''Argentinosaurushoz'' és a ''Puertasaurushoz'' hasonló)<ref name=calvoetal2007/> |

||

# ''[[Puertasaurus]]'': (az ''Argentinosaurushoz'' hasonló)<ref name=NSCA05>{{cite journal |last=Novas |first=Fernando E. |authorlink=Fernando Novas |coauthors=Salgado, Leonardo; Calvo, Jorge; and Agnolin, Federico |year=2005 |title=Giant titanosaur (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia |journal=Revisto del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, n.s. |volume=7 |issue=1 |pages=37–41 |url=http://www.macn.secyt.gov.ar/cont_Publicaciones/Rns-Vol07-1_37-41.pdf |accessdate=2007-03-04 }}</ref> |

# ''[[Puertasaurus]]'': (az ''Argentinosaurushoz'' hasonló)<ref name=NSCA05>{{cite journal |last=Novas |first=Fernando E. |authorlink=Fernando Novas |coauthors=Salgado, Leonardo; Calvo, Jorge; and Agnolin, Federico |year=2005 |title=Giant titanosaur (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia |journal=Revisto del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, n.s. |volume=7 |issue=1 |pages=37–41 |url=http://www.macn.secyt.gov.ar/cont_Publicaciones/Rns-Vol07-1_37-41.pdf |accessdate=2007-03-04 }}</ref> |

||

| 175. sor: | 175. sor: | ||

# ''[[Sauroposeidon]]'': 40-60 tonna<ref name="G.S.Paul2010"/><ref name=Wedeletal2000b/> |

# ''[[Sauroposeidon]]'': 40-60 tonna<ref name="G.S.Paul2010"/><ref name=Wedeletal2000b/> |

||

# ''[[Paralititan]]'': 20-59 tonna<ref name="G.S.Paul2010"/><ref name=burness&flannery2001>{{cite journal|author=Burness, G.P.|coauthors=Flannery, T.|year=2001|title=Dinosaurs, dragons, and dwarfs: The evolution of maximal body size|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|volume=98|issue=25|pages=14518–14523}}</ref> |

# ''[[Paralititan]]'': 20-59 tonna<ref name="G.S.Paul2010"/><ref name=burness&flannery2001>{{cite journal|author=Burness, G.P.|coauthors=Flannery, T.|year=2001|title=Dinosaurs, dragons, and dwarfs: The evolution of maximal body size|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|volume=98|issue=25|pages=14518–14523}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | # ''[[Brachiosaurus]]'': 28,7-56,3 tonna<ref name=taylor2009>{{cite journal|last=Taylor|first=M.P.|year=2009|title=A Re-evaluation of ''Brachiosaurus altithorax'' Riggs 1903 (Dinosauria, Sauropod) and its generic separation from ''Giraffatitan brancai'' (Janensh 1914)|journal=Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology|volume=29|issue=3|pages=787–806}}</ref><ref name="Bensonetal2014"/> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

# ''[[Ruyangosaurus]]'' 50 tonna<ref name=G.S.Paul2010/> |

# ''[[Ruyangosaurus]]'' 50 tonna<ref name=G.S.Paul2010/> |

||

# ''[[Camarasaurus]]'': 9,3-47 tonna<ref name="mazzettaetal2004"/><ref name= |

# ''[[Camarasaurus]]'': 9,3-47 tonna<ref name="mazzettaetal2004"/><ref name="foster">{{cite book |

||

|title=Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World |last=Foster|first=John |publisher=[[Indiana University Press]] |pages=201, 248 |year=2007 |isbn=978-0-253-34870-8}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | # ''[[Brachiosaurus]]'': 28,7- |

||

| ⚫ | |||

# ''[[Supersaurus]]'': 35-40 tonna<ref name=LHW07/> |

# ''[[Supersaurus]]'': 35-40 tonna<ref name=LHW07/> |

||

# ''[[Giraffatitan]]'': 19,9-39,5 tonna<ref name=dreadnoughtus_mass_2015/><ref name=mazzettaetal2004/> |

# ''[[Giraffatitan]]'': 19,9-39,5 tonna<ref name=dreadnoughtus_mass_2015/><ref name=mazzettaetal2004/> |

||

A lap 2016. február 6., 12:49-kori változata

A dinoszauruszok mérete a dinoszauruszkutatás egyik legérdekesebb szempontja a nagyközönség számára. Ez a szócikk a dinoszauruszok különféle csoportjainak legnagyobb és legkisebb tagjait sorolja fel, tömeg és hossz szerint rendezve.

A lista kizárólag nyilvánosságra hozott adatok alapján készült, és csak azokat a dinoszauruszokat tartalmazza, amelyeknek van hivatalos leírása. Megjegyzendő, hogy a dinoszauruszok feltételezett tömegei jóval pontatlanabbak lehetnek a becsült hosszuknál, mivel az utóbbi adathoz rendelkezésre állhat az állat teljes csontváza.

Általános rekordok

Legnehezebb dinoszauruszok

A tíz legnehezebb ismert dinoszaurusz, a megjelentetett tömegbecslések alapján. (Lásd még: A legnagyobb tömegű sauropodák)

- Amphicoelias: 122,4 tonna[1]

- Argentinosaurus: 50-90 tonna[2][3]

- Futalognkosaurus: (az Argentinosaurushoz és a Puertasaurushoz hasonló)[4]

- Puertasaurus: (az Argentinosaurushoz hasonló)[5]

- Antarctosaurus: 69-80 tonna[6][2]

- Apatosaurus: 16,4-80 tonna[7][8]

- Mamenchisaurus: 5-75 tonna[2]

- Notocolossus: 60,4 tonna[9]

- Sauroposeidon: 40-60 tonna[2][10]

- Paralititan: 20-59 tonna[2][11]

Leghosszabb dinoszauruszok

A tíz leghosszabb ismert dinoszaurusz, a megjelentetett hosszbecslések alapján. (Lásd még: A leghosszabb sauropodák)

- Amphicoelias: 58 méter[1]

- Argentinosaurus: 30-35 méter[1][12]

- Mamenchisaurus: 13-35 méter[13][2]

- Supersaurus: 33-34 méter[14]

- Sauroposeidon: 28-34 méter[1][15][10]

- Futalognkosaurus: 26-34 méter[16][4]

- Diplodocus: 24,9-33,5 méter[17][1]

- Antarctosaurus: 23-33 méter[1][18]

- Xinjiangtitan: 30-32 méter[19]

- Paralititan: 20-32 méter[2][18]

Legkönnyebb dinoszauruszok

A tíz legkönnyebb ismert nem madár dinoszaurusz, a megjelentetett tömegbecslések alapján.

- Anchiornis: 110-250 gramm[20][2]

- Parvicursor: 162 gramm[21]

- Epidexipteryx: 164-220 gramm[22][2]

- Compsognathus: 0,26-3,5 kilogramm[23][24]

- Juravenator: 0,34 kilogramm[24]

- Mei: 0,4 kilogramm [2]

- Jinfengopteryx: 0,4 kilogramm[2]

- Libagueino: 0,5 kilogramm[2]

- Fruitadens: 0,50-0,75 kilogramm[25]

- Sinosauropteryx: 0,55 kilogramm[24]

Legrövidebb dinoszauruszok

A tíz legrövidebb ismert nem madár dinoszaurusz, a megjelentetett hosszbecslések alapján.

- Epidexipteryx: 25-30 centiméter[22][2]

- Eosinopteryx: 30 centiméter[26]

- "Ornithomimus" minutus: 30 centiméter[18]

- Palaeopteryx: 30 centiméter[18]

- Parvicursor: 30-39 centiméter[18][21]

- Nqwebasaurus: 30-100 centiméter[18][2]

- Anchiornis: 34-40 centiméter[20][2]

- Microraptor: 42-120 centiméter[27][12]

- Mei: 45-70 centiméter[18][2]

- Xixianykus: 50 centiméter[18]

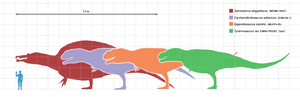

Theropodák

Az alábbi méretek lehetőség szerint határértékekkel lettek feltüntetve, a jelenleg rendelkezésre álló ismeretek alapján. Azokban az esetekben, ahol a határérték becslés alapján lett megállapítva, azok a források lettek megadva, amelyek a legszélsőbb értékeket tartalmazzák.

A leghosszabb theropodák

12 méteres hosszúság felett (farokkal együtt):

- Spinosaurus: 12,6-18 méter[24][28]

- Oxalaia: 12-14 méter[29]

- Carcharodontosaurus: 12-13,3 méter[30][24]

- Giganotosaurus: 12,2-13,2 méter[31][18]

- Chilantaisaurus: 11-13 méter[2][18]

- Saurophaganax: 10,5-13 méter[2][18]

- Tyrannosaurus : 12,3 méter[32]

- Tyrannotitan: 12,2 méter[18]

- Mapusaurus: a legmegbízhatóbb becslés szerint 10,2 méter, különálló maradványai összevethetők a 12,2 méteresre becsült Giganotosaurus leletanyagával[31]

- Acrocanthosaurus: 11-12 méter[2][18]

- Bahariasaurus: 11-12 méter[2][18]

- Kelmayisaurus: 10-12 méter[33]

- Torvosaurus: 9-12 méter[34][18]

- Allosaurus: 8,5-12 méter[35][18]

A legnagyobb tömegű theropodák

5 tonnánál nagyobb testtömegű állatok:

- Spinosaurus: 7-20,9 tonna[24][28]

- Carcharodontosaurus: 6,1-15,1 tonna[23][24]

- Giganotosaurus: 6,5-13,8 tonna[23][24]

- Tyrannosaurus: 6-10,2 tonna[24][36]

- Oxalaia: 5-7 tonna[29]

- Deinocheirus: 6,4 tonna[37]

- Acrocanthosaurus: 5,7-6,2 tonna[24][38]

- Chilantaisaurus: 2,5-6 tonna[39][40]

- Suchomimus: 3,8-5,2 tonna[23][24]

- Therizinosaurus: 5 tonna[2]

- Tarbosaurus: 4-5 tonna[2][41]

- Mapusaurus: 3-5 tonna[31][2]

A legrövidebb nem madár theropodák

Az eddig ismertté vált 60 centiméter alatti felnőttkori hosszúságú nem madár theropodák (nem számítva a lágy szöveteket és a tollas farkat):

- Epidexipteryx: 25-30 centiméter[22][2]

- Eosinopteryx: 30 centiméter[26]

- "Ornithomimus" minutus: 30 centiméter[18]

- Palaeopteryx: 30 centiméter[18]

- Parvicursor: 30-39 centiméter[18][21]

- Nqwebasaurus: 30-100 centiméter[18][2]

- Anchiornis: 34-40 centiméter[20][2]

- Microraptor: 42-120 centiméter[27][12]

- Mei: 45-70 centiméter[18][2]

- Xixianykus: 50 centiméter[18]

- Jinfengopteryx: 50-55 centiméter[42][2]

- Mahakala: 50-70 centiméter[43][2]

- Pamparaptor: 50-70 centiméter[44]

- Alwalkeria: 50-150 centiméter[18][2]

- Albinykus: 60 centiméter[18]

- Linhenykus: 60 centiméter[18]

- Pamparaptor: 60 centiméter[18]

- Shuvuuia: 60 centiméter[18]

- Ligabueino: 60-70 centiméter[2][45]

A legkönnyebb nem madár theropodák

Az eddig ismertté vált 1 kilogrammnál kisebb felnőttkori tömegű nem madár theropodák:

- Anchiornis: 110-250 gramm[20][2]

- Parvicursor: 162 gramm[21]

- Epidexipteryx: 164-220 gramm[22][2]

- Compsognathus: 0,26-3,5 kilogramm[23][24]

- Juravenator: 0,34 kilogramm[24]

- Mei: 0,4 kilogramm[2]

- Jinfengopteryx: 0,4 kilogramm[2]

- Ligabueino: 0,5 kilogramm[2]

- Fruitadens: 0,50-0,75 kilogramm[25]

- Sinosauropteryx: 0,55 kilogramm[24]

- Microraptor: 0,70-0,95 kilogramm[2][27]

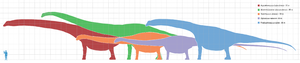

Sauropodák

A sauropodák mérete nehezen becsülhető meg, mivel maradványaik rendszerint töredékesek. Gyakran hiányzik a farkuk, ami hibás becsléshez vezethet. A tömeg megbecsléséhez a hossz négyzetét használják fel, így amennyiben a hossz téves, úgy a tömeg még inkább az lehet. A legbizonytalanabb (töredékes vagy hiányos leletek elemzése alapján történt) becslések kérdőjellel vannak megjelölve. Minden érték az adott forrásban szereplő legnagyobb becsült tömeg.

Megjegyzendő, hogy az óriás sauropodák két kategóriára oszthatók fel — a rövidebb, zömökebb és jóval nehezebb (főként titanosaurusok és brachiosauridák), valamint a hosszabb, de karcsúbb és könnyebb testfelépítésűekre (főként diplodocidák).

A leghosszabb sauropodák

A leghosszabb sauropodák (30 méteres hosszúság felett, nyakkal és farokkal együtt):

- Amphicoelias: 58 méter[1]

- Argentinosaurus: 30-35 méter[1][12]

- Mamenchisaurus: 13-35 méter[13][2]

- Supersaurus: 33-34 méter[14]

- Sauroposeidon: 28-34 méter[1][15][10]

- Futalognkosaurus: 26-34 méter[16][4]

- Diplodocus: 24,9-33,5 méter[17][1]

- Antarctosaurus: 23-33 méter[1][18]

- Xinjiangtitan: 30-32 méter[19]

- Paralititan: 20-32 méter[2][18]

- Alamosaurus: 30 méter[18]

- Puertasaurus: 30 méter[18]

- Ruyangosaurus: 30 méter[2]

- Turiasaurus: 30 méter[2]

- Daxiatitan: 23-30 méter[46][18]

- Hudiesaurus: 20-30 méter[18][47]

A legnagyobb tömegű sauropodák

20 tonnát meghaladó tömegű sauropodák:

- Amphicoelias: 122,4 tonna[1]

- Argentinosaurus: 50-90 tonna[2][3]

- Futalognkosaurus: (az Argentinosaurushoz és a Puertasaurushoz hasonló)[4]

- Puertasaurus: (az Argentinosaurushoz hasonló)[5]

- Antarctosaurus: 69-80 tonna[6][2]

- Apatosaurus: 16,4-80 tonna[7][8]

- Mamenchisaurus: 5-75 tonna [2]

- Notocolossus: 60,4 tonna[9]

- Sauroposeidon: 40-60 tonna[2][10]

- Paralititan: 20-59 tonna[2][11]

- Brachiosaurus: 28,7-56,3 tonna[48][3]

- Turiasaurus: 50-50,9 tonna[2][3]

- Ruyangosaurus 50 tonna[2]

- Camarasaurus: 9,3-47 tonna[6][49]

- Elaltitan: 42,8 tonna[3]

- Supersaurus: 35-40 tonna[14]

- Giraffatitan: 19,9-39,5 tonna[50][6]

- Diplodocus: 10-38,8 tonna[51][1]

- Dreadnoughtus: 22,1-38,2 tonna[50]

- Barosaurus: 20 tonna[23]

A legkisebb sauropodák

9 méteres vagy annál kisebb sauropodák:

- Ohmdenosaurus: 4 méter[18]

- Lirainosaurus: 4-6 méter[52]

- Blikanasaurus: 5 méter[18]

- Magyarosaurus: 5,3-6 méter[2][18]

- Europasaurus: 5,7-6,2 méter[2][18]

- Isanosaurus: 6,5 méter[53]

- Vulcanodon: 6,5-11 méter[2][18]

- Neuquensaurus: 7-7,5 méter[54][2]

- Antetonitrus: 8-10 méter, 1,5-2 méter a csípőnél[55]

- Shunosaurus: 8,7-11 méter[18][56]

- Zizhongosaurus 9 méter[18]

- Algosaurus: 9 méter[18][57]

- Kotasaurus: 9 méter[18]

- Volkheimeria: 9 méter[18]

- Zapalasaurus: 9 méter[2]

- Tazoudasaurus: 9-10 méter[18][58]

- Nigersaurus: 9-14,1 méter[2][17]

Ornithopodák

A leghosszabb ornithopodák

- Huaxiaosaurus: 18,7 méter[59]

- Shantungosaurus: 15-16,6 méter[18][60]

- Hypsibema: 15 méter[18]

- Edmontosaurus: 12-13 méter[61][62]

- Iguanodon: 10 méter, az I. bernissartensis esetében közel 13 méter[63]

- Magnapaulia: 12,5 méter[64]

- Anatotitan: 12 méter[65]

- Olorotitan: 12 méter[66]

- Saurolophus angustirostris: 12 méter[67]

- Kritosaurus sp.: 11 méter[68]

- Brachylophosaurus: 8,5-11 méter[2][18]

A legnagyobb tömegű ornithopodák

- Shantungosaurus: közel 16 tonna[69]

- Brachylophosaurus: 7 tonna[2]

- Lanzhousaurus: 6 tonna[2]

- Charonosaurus: 5 tonna[2]

- Barsboldia: 5 tonna[2]

- Edmontosaurus: 4 tonna[69]

- Hypacrosaurus: 4 tonna[69]

Ceratopsiák

A leghosszabb ceratopsiák

A leghosszabb ceratopsiák (7 méteres hosszúság felett, farokkal együtt):

- Eotriceratops: 8,5-9 méter[2][18]

- Triceratops: 8-9 méter[2][18]

- Torosaurus: 7,6-9 méter[70][18]

- Titanoceratops: 6,8-9 méter[71][18]

- Ojoceratops: 8 méter[18]

- Coahuilaceratops: 8 méter[18]

- Pentaceratops: 6-8 méter[72][18]

- Pachyrhinosaurus: 5-8 méter[2][18]

- Nedoceratops: 7,6 méter[18]

- Sinoceratops: 7 méter[18]

- Mojoceratops: 7 méter[18]

- Utahceratops: 6-7 méter[73]

- Vagaceratops: 4,5-7 méter[2][18]

- Arrhinoceratops: 4,5-7 méter[2][18]

- Agujaceratops: 4,3-7 méter[2][18]

- Chasmosaurus: 4,3-7 méter[2][18]

A legkisebb ceratopsiák

1 méteres vagy annál kisebb hosszúságú állatok:

- Yamaceratops: 50-150 centiméter[2][18]

- Archaeoceratops: 55-150 centiméter[74][18]

- Microceratus: 60 centiméter[18]

- Aquilops: 60 centiméter[75]

- Chaoyangsaurus: 60-100 centiméter[2][18]

- Xuanhuaceratops: 60-100 centiméter[2][18]

- Graciliceratops: 60-200 centiméter[18][76]

- Bagaceratops: 80-90 centiméter[2][18]

- Psittacosaurus: 90-200 centiméter[2][77]

- Ajkaceratops: 1 méter[78]

- Micropachycephalosaurus: 1 méter[79]

Pachycephalosaurusok

A leghosszabb pachycephalosaurusok

- Pachycephalosaurus: 4,5-7 méter[2][18]

A legkisebb pachycephalosaurusok

- Wannanosaurus: 60 centiméter[18]

- Colepiocephale: 1,8 méter[18]

Thyreophorák

A leghosszabb thyreophorák

- Stegosaurus: 6,5-9 méter[2][18]

- Ankylosaurus: 6,25-9 méter[80][18]

- Cedarpelta: 5-9 méter[81][18]

- Dacentrurus: 7-8 méter[82][18]

- Tarchia: 4,5-8 méter[2][18]

- Sauropelta: 5-7,6 méter[83][18]

- Dyoplosaurus: 7 méter[18]

- Tuojiangosaurus: 6,5-7 méter[2][18]

- Wuerhosaurus: 6,1-7 méter[2][18]

- Edmontonia: 6-7 méter[2][18]

- Jiangjunosaurus: 6-7 méter[2][18]

- Euoplocephalus: 5,5-7 méter[2][18]

- Saichania: 5,2-7 méter[2][18]

- Panoplosaurus: 5-7 méter[2][18]

- Shamosaurus: 5-7 méter[2][18]

- Gigantspinosaurus: 4,2-7 méter[2][18]

- Tsagantegia: 3,5-7 méter[2][18]

A legkisebb thyreophorák

- Liaoningosaurus: ?34 centiméter (fiatal egyed)[18]

- Tatisaurus:1,2 méter[18]

- Scutellosaurus: 1,2-1,3 méter[18][2]

- Dracopelta: 2 méter[18]

- Minmi: 2-3 méter[18][2]

Források és jegyzetek

Ez a szócikk részben vagy egészben a Dinosaur size című angol Wikipédia-szócikk ezen változatának fordításán alapul. Az eredeti cikk szerkesztőit annak laptörténete sorolja fel. Ez a jelzés csupán a megfogalmazás eredetét és a szerzői jogokat jelzi, nem szolgál a cikkben szereplő információk forrásmegjelöléseként.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). „Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation”, Albuquerque, 131–138. o, Kiadó: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press.

- ↑ a b c d e (2014) „Rates of Dinosaur Body Mass Evolution Indicate 170 Million Years of Sustained Ecological Innovation on the Avian Stem Lineage”. PLoS Biol 12 (5), e1001853. o. DOI:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001853.

- ↑ a b c d Calvo, J.O., Porfiri, J.D., González-Riga, B.J., and Kellner, A.W. (2007) "A new Cretaceous terrestrial ecosystem from Gondwana with the description of a new sauropod dinosaur". Anais Academia Brasileira Ciencia, 79(3): 529-41.[1]

- ↑ a b Novas, Fernando E., Salgado, Leonardo; Calvo, Jorge; and Agnolin, Federico (2005). „Giant titanosaur (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia”. Revisto del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, n.s. 7 (1), 37–41. o. (Hozzáférés: 2007. március 4.)

- ↑ a b c d Mazzetta, G.V., Christiansen, P., and Farina, R.A. (2004). „Giants and bizarres: body size of some southern South American Cretaceous dinosaurs”. Historical Biology 2004, 1–13. o.

- ↑ a b Henderson, D.M. (2006). „Burly Gaits: Centers of mass, stability, and the trackways of sauropod dinosaurs”. Journal of Vertebrae Paleontology 26 (4), 907–921. o. DOI:[907:BGCOMS2.0.CO;2 10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[907:BGCOMS]2.0.CO;2].

- ↑ a b Wedel, M. 2013.A giant, skeletally immature individual of Apatosaurus from the Morrison Formation of Oklahoma. The Annual Symposium of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Comparative Anatomy 2013:45.

- ↑ a b (2016) „A gigantic new dinosaur from Argentina and the evolution of the sauropod hind foot”. Scientific Reports 6, 19165. o. DOI:10.1038/srep19165.

- ↑ a b c d Wedel, Mathew J., Cifelli, Richard L.; Sanders, R. Kent (2000). „Osteology, paleobiology, and relationships of the sauropod dinosaur Sauroposeidon” (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 45, 343–3888. o. (Hozzáférés: 2010. szeptember 29.)

- ↑ a b Burness, G.P., Flannery, T. (2001). „Dinosaurs, dragons, and dwarfs: The evolution of maximal body size”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98 (25), 14518–14523. o.

- ↑ a b c d Benson, R.B.J., Brussatte, S. & Xu, X.. Prehistoric Life. London: Dorling Kindersley, 332. o. (2012)

- ↑ a b Young, C.C. (1954), On a new sauropod from Yiping, Szechuan, China. sinica, III(4), 481-514.

- ↑ a b c Lovelace, David M., Hartman, Scott A.; and Wahl, William R. (2007). „Morphology of a specimen of Supersaurus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Morrison Formation of Wyoming, and a re-evaluation of diplodocid phylogeny”. Arquivos do Museu Nacional 65 (4), 527–544. o.

- ↑ a b Wedel, Mathew J., Cifelli, Richard L. (2005. nyár). „Sauroposeidon: Oklahoma's Native Giant” (PDF). Oklahoma Geology Notes 65 (2), 40–57. o. (Hozzáférés: 2010. szeptember 29.)

- ↑ a b Calvo, J.O.; Juárez Valieri, R.D. & Porfiri, J.D. 2008. Re-sizing giants: estimation of body length of Futalognkosaurus dukei and implications for giant titanosaurian sauropods. 3° Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología de Vertebrados. Neuquén, Argentina.

- ↑ a b c Henderson, Donald (2013). „Sauropod Necks: Are They Really for Heat Loss?”. PLoS ONE 8 (10), e77108. o. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0077108. PMID 24204747.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck cl cm cn co cp Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix.

- ↑ a b (2013) „A new gigantic sauropod dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic of Shanshan, Xinjiang” (PDF). Global Geology 32 (3), 437–446. o. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1004-5589.2013.03.002.

- ↑ a b c d Xu, X., Zhao, Q., Norell, M., Sullivan, C., Hone, D., Erickson, G., Wang, X., Han, F. and Guo, Y. (2008. november 15.). „A new feathered maniraptoran dinosaur fossil that fills a morphological gap in avian origin”. Chinese Science Bulletin, 6. o.

- ↑ a b c d Which was the smallest dinosaur?. Royal Tyrrell Museum. (Hozzáférés: 2010. április 19.)

- ↑ a b c d Zhang, F., Zhou, Z., Xu, X., Wang, X. and Sullivan, C. (2008). „A bizarre Jurassic maniraptoran from China with elongate ribbon-like feathers Supplementary Information.”. Nature 455, 46. o. DOI:10.1038/nature07447.

- ↑ a b c d e f Seebacher, Frank. (2001). „A new method to calculate allometric length-mass relationships of dinosaurs”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 21 (1), 51–60. o. DOI:[0051:ANMTCA2.0.CO;2 10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0051:ANMTCA]2.0.CO;2].

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n François Therrien, Donald M. Henderson (2007). „My theropod is bigger than yours…or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27 (1), 108–115. o. DOI:[108:MTIBTY2.0.CO;2 10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[108:MTIBTY]2.0.CO;2]. (Hozzáférés: 2010. szeptember 29.)

- ↑ a b Butler, R.J., P.M. Galton, L.B. Porro, L.M. Chiappe, D.M. Henderson, and G.M. Erickson (2009). „Lower limits of ornithischian dinosaur body size inferred from a new Upper Jurassic heterodontosaurid from North America”. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2009.1494.

- ↑ a b Godefroit, P.; Demuynck, H.; Dyke, G.; Hu, D.; Escuillié, F. O.; Claeys, P. (2013). „Reduced plumage and flight ability of a new Jurassic paravian theropod from China”. Nature Communications 4, 1394. o. DOI:10.1038/ncomms2389. PMID 23340434.

- ↑ a b c Chatterjee, S., Templin, R.J. (2007). „Biplane wing planform and flight performance of the feathered dinosaur Microraptor gui” (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104 (5), 1576-1580. o. (Hozzáférés: 2010. szeptember 29.)

- ↑ a b Christiano dal Sasso, Simone Maganuco, Eric Buffetaut, Marco A. Mendez (2005). „New information on the skull of the enigmatic theropod Spinosaurus, with remarks on its sizes and affinities”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25 (4), 888–896. o. DOI:[0888:NIOTSO2.0.CO;2 10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0888:NIOTSO]2.0.CO;2]. (Hozzáférés: 2010. szeptember 29.)

- ↑ a b Kellner, Alexander W.A., Sergio A.K. Azevedeo, Elaine B. Machado, Luciana B. Carvalho and Deise D.R. Henriques (2011). „A new dinosaur (Theropoda, Spinosauridae) from the Cretaceous (Cenomanian) Alcântara Formation, Cajual Island, Brazil”. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 83 (1), 99–108. o. DOI:10.1590/S0001-37652011000100006. ISSN 0001-3765.

- ↑ Sereno, P. C., D. B. Dutheil, M. Iarochene, H. C. E. Larsson, G. H. Lyon, P. M. Magwene, C. A. Sidor, D. J. Varricchio, and J. A. Wilson (1996). „Predatory dinosaurs from the Sahara and the Late Cretaceous faunal differentiation”. Science 272, 986–991. o.

- ↑ a b c Rodolfo A. Coria, Philip J. Currie (2006). „A new carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina” (PDF). Geodiversitas 28 (1), 71–118. o. (Hozzáférés: 2010. szeptember 29.)

- ↑ Hutchinson J.R., Bates K.T., Molnar J., Allen V, Makovicky P.J. (2011). „A Computational Analysis of Limb and Body Dimensions in Tyrannosaurus rex with Implications for Locomotion, Ontogeny, and Growth”. PLoS ONE 6 (10), e26037. o. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0026037.

- ↑ Stephen L. Brusatte, Roger B. J. Benson and Xing Xu (2011). "A reassessment of Kelmayisaurus petrolicus, a large theropod dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of China" Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. in press: 65. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0125

- ↑ Paul, Gregory S.. Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. Simon & Schuster, 282. o. (1988). ISBN 0-671-61946-2

- ↑ Glut, Donald F.. Allosaurus, Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co, 105–117. o. (1997). ISBN 0-89950-917-7

- ↑ Christiansen, P, Fariña RA (2004). „Mass prediction in theropod dinosaurs”. Historical Biology 16 (2–4), 85–92. o. DOI:10.1080/08912960412331284313. (Hozzáférés: 2010. szeptember 29.)

- ↑ Lee, Yuong-Nam; Barsbold, Rinchen; Currie, Philip J.; Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu; Lee, Hang-Jae; Godefroit, Pascal; Escuillié, François; Chinzorig, Tsogtbaatar (2014. május 12.). „Resolving the long-standing enigmas of a giant ornithomimosaur Deinocheirus mirificus”. Nature 515, 257–260. o. DOI:10.1038/nature13874.

- ↑ Bates, K.T., Manning, P.L., Hodgetts, D. and Sellers, W.I. (2009). „Estimating Mass Properties of Dinosaurs Using Laser Imaging and 3D Computer Modelling”. PLoS ONE 4 (2), e4532. o. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0004532. (Hozzáférés: 2010. szeptember 29.)

- ↑ Benson R.B.J., Carrano M.T, Brusatte S.L. (2010). „A new clade of archaic large-bodied predatory dinosaurs (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) that survived to the latest Mesozoic”. Naturwissenschaften 97 (1), 71–78. o. DOI:10.1007/s00114-009-0614-x. PMID 19826771.

- ↑ Brusatte, S.L.; Chure, D.J.; Benson, R.B.J.; Xu, X. (2010). „The osteology of Shaochilong maortuensis, a carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Asia”. Zootaxa 2334, 1–46. o.

- ↑ Valkenburgh, B. and Molnar, R.E. (2002). „Dinosaurian and mammalian predators compared”. Paleobiology 28 (4), 527–543. o.

- ↑ Q. Ji, S. Ji, J. Lu, H. You, W. Chen, Y. Liu (2005). „First avialan bird from China (Jinfengopteryx elegans gen. et sp. nov.)”. Geological Bulletin of China 24 (3), 197–205. o.

- ↑ Alan H. Turner, Diego Pol, Julia A. Clarke, Gregory M. Erickson, Mark A. Norell (2007. szeptember 7.). „A basal dromaeosaurid and size evolution preceding avian flight” (PDF). Science 317 (5843), 1378–1381. o. DOI:10.1126/science.1144066. PMID 17823350. (Hozzáférés: 2010. szeptember 29.)

- ↑ Porfiri, Juan D. (2011). „A new small deinonychosaur (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina”. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 83 (1), 109–116. o. DOI:10.1590/S0001-37652011000100007.

- ↑ Carrano, M.T., Loewen, M.A. and Sertic, J.J.W. (2011). "New Materials of Masiakasaurus knopfleri Sampson, Carrano, and Forster, 2001, and Implications for the Morphology of the Noasauridae (Theropoda: Ceratosauria). Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology, 95: 53pp.

- ↑ You, H.-L., Li, D.-Q.; Zhou, L.-Q.; and Ji, Q (2008). „Daxiatitan binglingi: a giant sauropod dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of China”. Gansu Geology 17 (4), 1–10. o.

- ↑ Dong, Z..szerk.: Dong, Z.: A gigantic sauropod (Hudiesaurus sinojapanorum gen. et sp. nov.) from the Turpan Basin, China, Sino-Japanese Silk Road Dinosaur Expedition. Beijing: China Ocean Press, 102–110. o. (1997)

- ↑ Taylor, M.P. (2009). „A Re-evaluation of Brachiosaurus altithorax Riggs 1903 (Dinosauria, Sauropod) and its generic separation from Giraffatitan brancai (Janensh 1914)”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (3), 787–806. o.

- ↑ Foster, John. Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press, 201, 248. o. (2007). ISBN 978-0-253-34870-8

- ↑ a b Bates, Karl T. (2015. június 1.). „Downsizing a giant: re-evaluating Dreadnoughtus body mass”. Biology Letters 11 (6), 20150215. o. DOI:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0215. ISSN 1744-9561. PMID 26063751.

- ↑ Dodson, P., Behrensmeyer, A.K., Bakker, R.T., and McIntosh, J.S. (1980). „Taphonomy and paleoecology of the dinosaur beds of the Jurassic Morrison Formation”. Paleobiology 6, 208–232. o.

- ↑ V. D. Diaz, X. P. Suberpiola, and J. L. Sanz. 2013. Appendicular skeleton and dermal armour of the Late Cretaceous titanosaur Lirainosaurus astibia (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from Spain. Palaeontologia Electronica 16(2):19A

- ↑ Buffetaut, E. (2000). „The earliest known sauropod dinosaur”. Nature 407 (6800), 72–74. o. DOI:10.1038/35024060. PMID 10993074.

- ↑ Wilson. J. A. (2006): An Overview of Titanosaur Evolution and Phylogeny. En (Colectivo Arqueológico-Paleontológico Salense, Ed.): Actas de las III Jornadas sobre Dinosaurios y su Entorno. 169-190. Salas de los Infantes, Burgos, España. 169

- ↑ Yates, A.M. & Kitching, J.W. 2003. The earliest known sauropod dinosaur and the first steps towards sauropod locomotion. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 270: 1753-1758.

- ↑ Y. Zhang. 1988. The Middle Jurassic dinosaur fauna from Dashapu, Zigong, Sichuan. Vol. III. Sauropod dinosaur (1). Shunosaurus. Sichuan Publishing House of Science and Technology, Chengdu 1-89

- ↑ Lessem, Don. The Dinosaur Society's dinosaur encyclopedia, illust. by Tracy Ford, New York: Random House, 16. o. (1993). ISBN 0-679-41770-2

- ↑ Peyer, Karin, and Ronan Allain. "A reconstruction of Tazoudasaurus naimi (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the late Early Jurassic of Morocco." Historical Biology 22.1-3 (2010): 134-141.

- ↑ Zhao Xijin, Wang Kebai, & Li Dunjing (2011). „Huaxiaosaurus aigahtens”. Geological Bulletin of China 30 (11), 1671–1688. o.

- ↑ X. Zhao, D. Li, G. Han, H. Hao, F. Liu, L. Li, X. Fang (2007). „Zhuchengosaurus maximus from Shandong Province”. Acta Geoscientia Sinica 28 (2), 111–122. o.

- ↑ Donald F. Glut. Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co, 389–396. o. (1997). ISBN 0-89950-917-7

- ↑ David Lambert, and the Diagram Group. Edmontosaurus, The Dinosaur Data Book. New York: Avon Books, 60. o. (1990). ISBN 0-380-75896-3

- ↑ Darren Naish, David M. Martill. Ornithopod dinosaurs, Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight. London: The Palaeontological Association, 60–132. o. (2001). ISBN 0-901702-72-2

- ↑ Prieto-Márquez, A.; Chiappe, L. M.; Joshi, S. H. Dodson, Peter, ed. (2012). „The lambeosaurine dinosaur Magnapaulia laticaudus from the Late Cretaceous of Baja California, Northwestern Mexico”. PLoS ONE 7 (6), e38207. o. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0038207. PMID 22719869.

- ↑ Hans-Dieter Sues.szerk.: James Orville Farlow, M. K. Brett-Surman: ornithopods, The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 338. o. (1997). ISBN 0-253-33349-0

- ↑ Dixon Dougal. The Complete Book of Dinosaurs. London: Anness Publishing Ltd., 219. o. (2006). ISBN 0-681-37578-7

- ↑ Donald F. Glut. Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co, 788–789. o. (1997). ISBN 0-89950-917-7

- ↑ James I. Kirkland, René Hernández-Rivera, Terry Gates, Gregory S. Paul; Sterling Nesbitt, Claudia Inés Serrano-Brañas, Juan Pablo Garcia-de la Garza.szerk.: S. G. Lucas, Robert M. Sullivan: Large hadrosaurine dinosaurs from the latest Campanian of Coahuila, Mexico, Late Cretaceous Vertebrates from the Western Interior, New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 35. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, 299–315. o. (2006)

- ↑ a b c John R. Horner, David B. Weishampel, Catherine A. Forster.szerk.: David B. Weishampel; Peter Dodson, Halszka Osmólska: Hadrosauridae, The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press, 438–463. o. (2004). ISBN 0-520-24209-2

- ↑ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2008) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages Supplementary Information

- ↑ Lehman, T.M. (1998). „A gigantic skull and skeleton of the horned dinosaur Pentaceratops sternbergi”. From New Mexico: Journal of Paleontology, 72 (5), 894–906. o.

- ↑ C. Wiman, 1930, "Über Ceratopsia aus der Oberen Kreide in New Mexico", Nova Acta Regiae Societatis Scientiarum Upsaliensis, Series 4 7(2): 1-19

- ↑ „Descubren nuevos dinosaurios con cuernos”, La Nación , 2010. szeptember 26. (spanyol nyelvű)

- ↑ You, Hai-Lu. A new species of Archaeoceratops (Dinosauria: Neoceratopsia) from the Early Cretaceous of the Mazongshan area, northwestern China, New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 59–67. o. (2010). ISBN 978-0-253-35358-0

- ↑ Andrew A., Farke; Maxwell, W. Desmond; Cifelli, Richard L.; Wedel, Mathew J. (2014. december 10.). „A Ceratopsian Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Western North America, and the Biogeography of Neoceratopsia”. PLoS ONE 9 (12). DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0112055.

- ↑ Sereno, P.C.2000.. „"The fossil record, systematics and evolution of pachycephalosaurs and ceratopsians from Asia." The age of dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia:480–516.”.

- ↑ Sereno, Paul C. (1997). Psittacosauridae. In: Currie, Philip J. & Padian, Kevin P. (Eds.). The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. San Diego: Academic Press. Pp. 611–613.

- ↑ Ősi, Attila (2010. május 27.). „A Late Cretaceous ceratopsian dinosaur from Europe with Asian affinities”. Nature 465 (7297), 466–468. o. DOI:10.1038/nature09019. PMID 20505726.

- ↑ Butler, R.J. and Zhao, Q. (2009). „The small-bodied ornithischian dinosaurs Micropachycephalosaurus hongtuyanensis and Wannanosaurus yansiensis from the Late Cretaceous of China”. Cretaceous Research 30 (1), 63–77. o. DOI:10.1016/j.cretres.2008.03.002.

- ↑ Carpenter, K. (2004). „Redescription of Ankylosaurus magniventris Brown 1908 (Ankylosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Western Interior of North America”. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 41, 961–986. o. DOI:10.1139/e04-043. (Hozzáférés: 2010. szeptember 29.)

- ↑ Carpenter, Kenneth (2008). „Ankylosaurs from the Price River Quarries, Cedar Mountain Formation (Lower Cretaceous), east-central Utah”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28 (4), 1089–1101. o. DOI:10.1671/0272-4634-28.4.1089.

- ↑ Galton, Peter M.; Upchurch, Paul, 2004, "Stegosauria" In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd edition, Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 344-345

- ↑ Carpenter, Kenneth. (1984). „Skeletal reconstruction and life restoration of Sauropelta (Ankylosauria: Nodosauridae) from the Cretaceous of North America”. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 21 (12), 1491–1498. o. DOI:10.1139/e84-154.

- Gregory S. Paul (1997). „Dinosaur models: the good, the bad, and using them to estimate the mass of dinosaurs”. Dinofest International 1997, 129–154. o.

Külső hivatkozások

- Robin Lloyd: The Biggest Carnivore: Dinosaur History Rewritten, 2006. március 1. (Hozzáférés: 2010. szeptember 29.)

- Mickey Mortimer: And the Largest Theropod Is…. Dinosaur Mailing List, 2003. július 21. (Hozzáférés: 2010. szeptember 29.)