„Shapley–Curtis-vita” változatai közötti eltérés

| [nem ellenőrzött változat] | [nem ellenőrzött változat] |

Nincs szerkesztési összefoglaló |

a History of astronomy kategória eltávolítva; Csillagászattörténet kategória hozzáadva (a HotCattel) |

||

| 33. sor: | 33. sor: | ||

*[http://antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov/diamond_jubilee/debate20.html The Shapley–Curtis Debate in 1920]—resources related to the debate at the [[NASA]] website |

*[http://antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov/diamond_jubilee/debate20.html The Shapley–Curtis Debate in 1920]—resources related to the debate at the [[NASA]] website |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Csillagászattörténet]] |

||

[[Category:Debates]] |

[[Category:Debates]] |

||

[[Category:Cosmology]] |

[[Category:Cosmology]] |

||

A lap 2011. december 31., 11:31-kori változata

In astronomy, the Great Debate, also called the Shapley–Curtis Debate, was an influential debate between the astronomers Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis which concerned the nature of spiral nebulae and the size of the universe. The basic issue under debate was whether distant nebulae were relatively small and lay within our own galaxy or whether they were large, independent galaxies. The debate took place on 26 April 1920, in the Baird auditorium of the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. The two scientists first presented independent technical papers about "The Scale of the Universe" during the day and then took part in a joint discussion that evening. Much of the lore of the Great Debate grew out of two papers published by Shapley and Curtis in the May 1921 issue of the Bulletin of the National Research Council. The published papers each included counter arguments to the position advocated by the other scientist at the 1920 meeting.

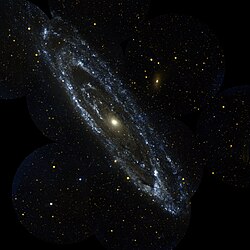

Shapley was arguing in favor of the Milky Way as the entirety of the universe. He believed galaxies such as Andromeda and the Spiral Nebulae were simply part of the Milky Way. He could back up this claim by citing relative sizes—if Andromeda was not part of the Milky Way, then its distance must have been on the order of 108 light years—a span most astronomers would not accept. Adriaan van Maanen was also providing evidence to Shapley's argument. Van Maanen was a well-respected astronomer of the time who claimed he had observed the Pinwheel Galaxy rotating. If the Pinwheel Galaxy were in fact a distinct galaxy and could be observed to be rotating on a timescale of years, its orbital velocity would be enormous and there would clearly be a violation of the universal speed limit, the speed of light. Also used to back up his claims was the observation of a nova in the Andromeda galaxy that had temporarily outshone the nucleus of the galaxy itself, a seemingly absurd amount of energy for a normal nova. Thus, the nova and the galaxy itself must be within our own galaxy since, if Andromeda were a galaxy in its own right, the nova would have had to have been unthinkably bright in order to be seen from so far away.

Curtis on the other side contended that Andromeda and other such nebulae were separate galaxies, or "Island universes" (a term invented by the philosopher Immanuel Kant, who also believed that the spiral nebulae were extragalactic.). He showed that there were more novae in Andromeda than in the Milky Way. From this he could ask why there were more novae in one small section of the galaxy than the other sections of the galaxy, if Andromeda was not a separate galaxy but simply a nebula within our galaxy. This led to supporting Andromeda as a separate galaxy with its own signature age and rate of novae occurrences. He also cited dark lanes present in other galaxies similar to the dust clouds found in our own galaxy and massive doppler shifts found in other galaxies.

Curtis stated that if van Maanen's observation of the Pinwheel Galaxy rotating were correct, he himself would have been wrong about the scale of the universe and that the Milky Way would fully encompass it.

After the debate

It later became apparent that van Maanen's observations were incorrect—one can not actually see the Pinwheel Galaxy rotate during a human lifespan.

Due to the work of Edwin Hubble, it is now known that the Milky Way is only one of hundreds of billions of galaxies in the visible universe, proving Curtis the more accurate party in the debate in that respect. Also, it is now known that the nova Shapley referred to in his arguments was in fact a supernova, which do indeed temporarily outshine the combined output of an entire galaxy. On other points the results were mixed (the actual size of the Milky Way is in between the sizes proposed by Shapley and Curtis), or in favor of Shapley (Curtis' galaxy was centered on the Sun, while Shapley correctly placed the Sun in the outer regions on the galaxy).[1]

1920 körül éles vita tárgya volt a csillagászok között, hogy más galaxisok a Tejútrendszeren belül, vagy kívül vannak-e. A kisebb távolság mellett érvelők szerint ha kívül vannak, akkor az Androméda-galaxis távolsága a 108 fényév nagyságrendjébe esne, és a csillagászok ezt nem fogadták el. A Szélkerék-Galaxis spirálkarjának forgási sebessége megközelítette vagy meghaladta volna a fénysebességet, amiről abban az időben már ismert volt, hogy nem léphető túl.

Az ellentábor rámutatott, hogy az Andromédában több nóva van, mint a Tejútrendszerben (ami ellentmondás, ha az Androméda a Tejútrendszeren belül lenne). A forgási sebesség meghatározásában kételkedtek (ez valóban téves adat volt, a Szélkerék-Galaxis forgása egy emberöltőn belül nem észlelhető).

A nagy távolságok meghatározására vonatkozó kétféle elképzelés közötti ellentét miatt az Amerikai Tudományos Akadémia ülést szervezett, amit 1920 áprilisában tartottak Washingtonban. Tárgya ez volt: „A világegyetem mérete”. A vita előtt elismeréseket adtak át, ami azzal járt, hogy az amerikai tudományos élet jó néhány jeles képviselője jelen volt az ülésen. Az elnöki asztalnál foglalt helyet egy európai vendég, Albert Einstein, akinek általános relativitáselméletét az előző évben igazolták egy napfogyatkozás alkalmával, ami lehetővé tette, hogy megfigyelhessék a fény útjának „meggörbülését” gravitációs térben (ti. a Nap közelében). Henrietta Swan Leavitt nem volt jelen a megbeszélésen - annak ellenére, hogy a vita az őáltala felfedezett periódus-fényesség összefüggésből indult ki, illetve az erre épülő távolságmeghatározásokon folyt - hiszen sem megfelelő szakmai pozíciója, sem megfelelő végzettsége nem volt hozzá, hogy meghívják. Voltak azonban néhányan, akik azt gondolták róla, hogy briliáns elme, és ezek között volt Harlow Shapley is.

Egy másik személy, aki hiányzott a megbeszélésről (amit később „the Great Debate”, am. „nagy vita” néven emlegettek), a 38-éves Edwin Powell Hubble volt, aki úgy gondolta, helyes Curtisnek az az elképzelése, hogy több galaxis létezik. Hubble a Mount Wilsonban dolgozott, Kaliforniában, ahol a korábbi években Shapley is tevékenykedett, így ott kollégák voltak és ismerték, de nem kedvelték egymást. Shapley Missouri államból származott, és volt benne egy adag „falusi fiú” ingerlékenység, míg Hubble felsőbb társadalmi osztályból származó, Rhodes-ösztöndíjjal végzett tudós volt. Shapley lenézte Hubble bizonyítványait; azt, hogy a nála kissé fiatalabb férfi eredetiben olvasott klasszikusokat, köztük görög és latin szerzők műveit, dilettantizmusnak tekintette. Mégis Edwin Hubble volt az, aki a Leavitt által felfedezett összefüggést a cefeidák periódusa és fényessége között a leginkább kiterjesztette.

External links

- The Shapley–Curtis Debate in 1920—resources related to the debate at the NASA website

Jegyzetek

- ↑ Why the 'Great Debate' was important. NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. (Hozzáférés: 2009. október 16.)